Innovazione e migrazione intellettuale, chi sei, chi conosci e il valore del network

Report - 17/12/2023

di Redazione Fast News

Oltre le Competenze: rivalutare l’immigrazione di talenti nell’era dell’innovazione e del progresso globale. ll professor Ram Mudambi esplora temi cruciali come l’integrazione del capitale umano e sociale nell’immigrazione ad alta qualifica, offrendo spunti preziosi e prospettive nuove. La sua tesi si concentra su come le politiche di immigrazione possono essere ottimizzate per massimizzare i benefici dell’immigrazione altamente qualificata per i paesi di destinazione e di origine. La lezione è stata registrata il 10 novembre 2023 all’Università di Palermo facoltà di Economia e Commercio, nell’ambito delle attività collaterali al Premio Innovazione Sicilia 2023.

Ram Mudambi [00:05:43] Thank you, Sebastiano, for that very kind introduction. And I thank the department For having me here. Mi dispiace che il mio italiano sia molto pessimo! Quindi io parlo in inglese, lentamente. So much for that, my attempt at starting off in Italian. But we’ll first move on. I’ll try and speak slowly and hopefully all of you at the back can read the writing.

Ram Mudambi [00:06:33] Quick outline. Today I’m going to talk about high skill migration. That’s going to be my main topic. We’ll start off by giving you the context. I’ll give you some vignette, some short stories that we’ll talk a little bit about. Restrictions on high skill migration and the associated costs. I’ll give a quick, little outline of policy on high skill migration in rich countries, including Italy. And summarise for you what we know in the literature, which is that there are two basic approaches adopted in the world in rich countries, and we call them the supply side approach and the demand side approach. We’ll go over those very quickly. I will demonstrate to you that all the current approaches to high skill migration focus on human capital. That is the skill or the skill level of the individual. That will lead me into a discussion of how we should value high skill migrants. Human capital that is basically valuing the individual and social capital, which is valuing the individual’s tie in connection. I’ll then give you a quick thumbnail summary of research papers we published some years ago where we demonstrate empirically the existence of bridging ties in social capital, in creating innovation. This will then lead me to proposing to you a two dimensional model of valuing high skilled migrants. And I’ll conclude with showing you some U.S. data, some Italian data on the sub optimality of current policy. And that’ll lead me to some concluding remarks. Okay. So I have a lot of slides, but I’m going to go through them fairly quickly because most of them are for the purposes of illustration and demonstration.

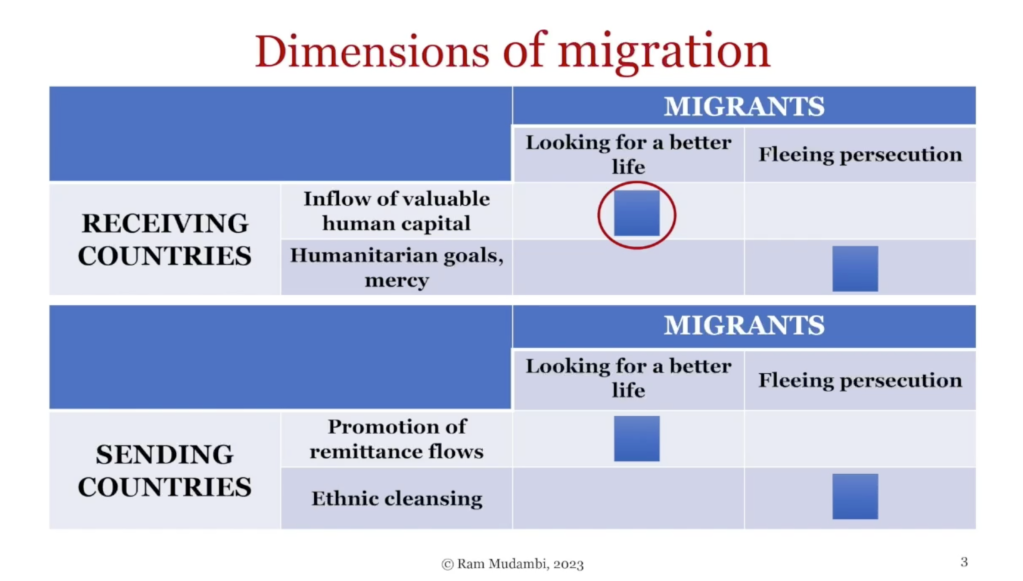

Ram Mudambi [00:09:06] So let’s start off by talking about dimensions of migration that will give you a context of exactly what I am talking about and what I am not talking about. If we look at migrants, we could look at and again, my wife likes to say if you do any paper in management, it must have a two by two matrix. And so I must have a two by two matrix here. So to look at our matrix has migrant the decision of the person, the migrant, on one axis and the perspective of the receiving country on the vertical axis and the perspective of the sending country also. For the migrants move for two fundamental reasons, on the basis of the United Nations data. This is looking for a better life or fleeing persecution. Receiving countries mainly are rich countries, OECD countries, including Italy. They have two perspectives on valuing migrants. One is looking at them as valuable inflow of human capital. Or, viewing them as objects of humanitarian concern or mercy. Very often in politics and policy space these are confused and their order is mixed together, where they say migrants are good but we must also be worried about giving mercy. But these are separate goals, separate objectives, and we should therefore view them separately, because the kinds of migrants that we should look at as flows of human capital are mainly those who are looking for a better life. And those we should be worried about from the perspective of mercy or humanity are fleeing persecution. If we look at the perspective of the sending country the same story. If I’m a poor country. I’m sending migrants abroad, if my migrants are looking for a better life, then I view them as they will send money back. They will send remittances back to my country. That is the short term view the sending countries take. Alternatively, and this is of course, the very dark side, if you have the sending country when they are sending people abroad, fleeing persecution, they are thinking we don’t want these people. Ethnic cleansing. Then they send them away. Right. However, I am studying only that box. So everything else I am not studying. Okay, so all of these are important. All of those boxes are important, but they are subject for another paper, another study. [00:12:26]I am only studying high skill migrants, valuable human capital who are moving, looking for a better life. [8.3s] Okay. That’s the only thing I’m not looking about humanity. All of that is not part of my study or my presentation today. I want to make that very clear in the beginning.

Ram Mudambi [00:12:46] High school migrants now contribute disproportionately to knowledge intensive occupations in rich countries. The US, for example, we find that a very high percentage of patents are associated with migrants. Migrants account for a very high percentage of skilled workers in countries like Switzerland or Australia. William Kerr, at Harvard, has a very famous book where he shows that migrants are so important to the entrepreneurial culture and entrepreneurial business outcomes in the United States. Recent research by people like Mayda, Orefice and Santoni look for example at European Union data and they also show that migrants are associated with dramatic increases in innovation output and they do a nice definitive study showing causation and so on and they’re able to show that if you have more migrants, you get more innovation. This is with French data.

Ram Mudambi [00:13:51] The picture in Italy is a little less encouraging. Most recently, for example, we find that a lot of high skilled migrants in Italy who enter under the Italian points system are often underemployed. Their skills are not appropriately deployed within the economy. Italy doesn’t receive as much of an innovation value as it perhaps should, for many reasons. And this is particularly true for migrants to Italy from outside the EU. Outside the EU, which is basically the vast majority of the world’s population. The migrants tend to get excluded from health care, skilled professions, language, barriers to entry, a big issue and bureaucracy. The two big thing that the EU and the UN both find in the case of Italy, bureaucracy and language tend to be a big problem, as in my own case. However, even countries that have gained a lot major gains from high skilled migrants, even in these countries, we find that restrictions on migration are rising. The United States, New Zealand, United Kingdom, Australia, Singapore, all of these countries have gained enormously from high skilled migrants. But even there, we find restrictions. The US 2017-2020, we find increasing restrictions on high skilled migration. In Australia, 2017, laws were passed restricting high skilled migration. In the UK, both in 2011 and in 2015. Singapore 2016 and Singapore is particularly interesting because something like almost half the Singapore population are migrants. The entire island is made up of migrants and yet they are restricting high skilled migrants. New Zealand by 2017 also passed laws restricting high skill migration. Restricting high skilled migration is costly. It erodes the value of firms, it increases outsourcing. We show that in some recent paper that we have, and it hurts the productivity and novelty of innovation. When you restrict migration, we show in a paper that we have currently ongoing that both the novelty and the output of innovation goes down.

Ram Mudambi [00:16:29] So how can our research inform immigration policy? We know that most of the restrictions on high skilled migration come from populism, [00:16:52]populist restrictions. [0.7s] And this is based on politics, not economics. However, when we look at the researchers today, as I showed you, the French researcher, the people looking at American data, Bill Kerr from Harvard and so on, all of this research tends to take, what we argue, is too simplistic a view of migrants. Even the most well cited work like Bill Kerr, for example, at Harvard, they take a binary approach. Native born, migrant, native born or migrant, but all migrants in one bucket altogether. They treat all migrants as the same as a homogeneous group. And this, we would argue, doesn’t distinguish between the differential value of different migrant groups and it contributes to populism because people say, well, actually, I don’t really care about these migrants because, as I can see in my neighbourhood, these migrants don’t integrate. But all of them are not the same. So we argue that this can be corrected. [00:18:14]We can reduce populism by having a better policy. [3.1s] The current high skill migration, we argue, focuses exclusively on human capital and only on the individual. There are two main approaches as I pointed out, supply side and demand side. The supply side approach is typically used in most of Europe. Most of the EU, including Italy, the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and so on. The demand side is used mainly in the U.S.. The supply side tend to be implemented from point systems. Every individual is given points, like the Italian academic system where you get points for promotion or points for job and so on. Look at your CV or convert it to point. Point systems for immigration are the same. They look at the CV, the resume, and you convert that into points and if you get more than certain number of points, you’re allowed to enter. But this does not connect the migrant to a job. This is one of the problems we see in Italy, for example. Somebody gets the point. They enter the country, but they don’t have a job. If they don’t fit the labour market, they won’t get a job or they’ll be underemployed. We see this in Canada a lot. However, in the U.S., the demand side system is driven by firms. You can’t enter until a firm gives you a job at the appropriate level. For example, to get a H-1b visa in the U.S., you need to get a job which would pay you at least 130,000 U.S. dollars. It’s about €120,000 per year. If you get a job offer less than €100,000 immediately, you are not qualified. You cannot enter. So that means you have to have high skill. The company should say you are really valuable and then you enter. Then the government says, okay, we’ll consider you and put you in the green card queue and then you can enter. You enter with a job. So migrants don’t enter without a job. The Swiss system, for example, look at your degree from University of Higher Education, a number of years of professional experience. But in Italy, again, this is this is these are rules that will come into force on the 23rd, which is another two weeks from now. These are the rules for Italy, you look for a level of degree, five years of professional experience, etc.. Australia minimum 65 points. Points are given for age, education, English language skills, employment experience in Australia and so on. Canada has the CRS system of comprehensive rankings. Score consists of core human capital, which is again, age, official language proficiency, mainly French, spousal factors – if you have a spouse that is highly qualified, ability to use language, etc.. The UK, again, minimum 70 points are necessary. You get a little bit of a mixed system. You need a job offer as well. But you also need to have skills in a job which is designated as a scarcity. A PhD, for example, is considered valuable, particularly in STEM area and so on. In the U.S., of course you have to have a work visa. You must have employment, an employer who is willing to sponsor you and so on. And that means you can enter one of the five categories. EB one to EB five.

Ram Mudambi [00:21:46] Okay. So, we’ve demonstrated here that basically that even the US, all of these systems focus only on the individual. Right? I’ve given you some examples. You could take many more. If you look at Austria, all the EU and Norway, all of them have the same kind of picture. Now let’s move on to perspectives on high skill migration. What exactly is going on here? The mass movement of human capital, high skill human capital from poorer, less developed countries to richer, more developed countries – this is basically the standard movement – this is where almost most of the millions and millions of people this is the category that go from poor countries to rich countries. Not a lot of people going the other way. So there’s been a major concern from the 1960s onwards. It’s been going on for much longer than all of you are alive, probably even before your parents were born, perhaps. But this led to the notion or the terminology both in academics as well as in policy as well as in politics of [00:23:02]brain drain, [0.4s] the idea of being a regressive wealth transfer summarised in that one sentence: The poorest people in the poor countries pay taxes, mainly regressive taxes like sales taxes to heavily subsidise the education of their middle class and upper class countrymen and women who then migrate to rich countries to work for higher wages in these rich countries. So, as you can see, this is a double subsidy because it is a subsidy within the country, poor people in a poor country, subsidising the less poor people and the poor countries sending people to rich countries. So this is basically regressive, regressive, regressive, three levels of regression here where you take money from the poorest of the poor people and you’re creating wealth for the richest of the rich. That’s the idea of the brain drain. Very seductive, very powerful. Fortunately, exit taxes, which were proposed on the basis of the brain drain, were not put in place because the alternative explanation is or is it a brain circulation which led to rapid growth? Because the interesting feature is that there is correlation between countries that exported brains to rich countries in the 1960s and 1970s, and those are the same countries that became the fastest growing emerging market economies from the 1990s onwards. Anna Lee Saxenian, who is from Berkeley, who is the original originator of the term [00:24:55]brain circulation. [0.5s] She started by studying in great detail the experiences of Taiwan which was a very poor country in the 1960s and 1970s and exported its most intelligent people, many of whom became engineers in what was to become Silicon Valley. So Saxenian documented in very careful detail that it was the return connectivity of these Taiwanese settled in the US with their home country of Taiwan through a circulatory process – some of them came back, some of them constantly maintained to home started companies, etc – that led to incredible an entrepreneurial boom in Taiwan. With the result that by the late 1990s, Taiwan became the world’s centre number one producer of PCs personal computer. Established almost entirely on the basis of Taiwanese engineers connected with the United States. This is her book, [00:26:11]The Global Argonauts, [0.4s] as she focuses on the notion of entrepreneurship, high skilled migrants from emerging economies, starting new global entrepreneurial businesses, linking their home country with their country of residence or country of employment. If you look at the United States, which is the most open entrepreneurial economy in the world, the leading home of unicorn companies – companies that achieved a market value of 1 billion U.S. dollars within 18 months of foundation – we see that an incredible number of these unicorns are started by individuals from emerging economies. And of course, you see again, those who started more than one, are also connected with the same same countries. Now what we see, however – unfortunately, you couldn’t see the country on this slide, you can see the flags – India, Israel, the UK, Canada, China, France, Germany, Russia, Ukraine and Iran, the country along that axis. And we see many of the same countries are home to home-grown unicorns. So brain circulation links the entrepreneurial ecosystems of the two countries together, of the migrants’ country of origin and country of destination. The origin countries of U.S. unicorn founders are themselves leaders on the global unicorn list.

Ram Mudambi [00:28:24] I’m going to spend a few minutes talking to you about relates to the employment. At least Saxenian talked about start-ups entrepreneurial companies. What I’m going to talk to you about are giant or bigger companies, multinational enterprises like Intel, Microsoft, Google, GE and so on, and the employment in these companies of migrant high skilled worker. There’s the apocryphal story of the genesis of the Bangalore software cluster. Now, I have studied Bangalore in India for the last 14 years or so. And the stories you hear over and over about the foundation of the Bangalore software cluster, all of them come back to the same starting point. Because the fact is that the very first subsidiary High Knowledge R&D unit set up in India was in fact in 1985 by Texas Instruments, an American multibillion dollar high tech company. And they are the first foreign company to set up an R&D operation in India. And they did so in 1985. Between 1985 and 1990, every major American high tech company set up and many European, including companies like Philips and Alcatel, Alstom and many others. All of these companies within 5 to 6 years, 1985-1991, all of them had set up R&D operations in and around Bangalore. Because of course companies learn from other companies. They realise this is a valuable, cheap, high skilled labour that we can hire and they also help these operations. But what is not often told is that all of the U.S. multinational companies that set up R&D operations in India, the prime decision makers in almost every single case, were [00:31:02]people who were born in India. [2.3s] Senior executives, people who have migrated from India to the United States, become senior in the big companies, and then made decisions to put R&D operations in their home country. This is brain circulation in action. Just because somebody leaves and migrate to another country doesn’t mean that they cut all ties with that country forever. The connections are always there. The connections are there for life as long as that person will live. And they are valuable connections, extremely valuable connections for the sending country. So now the duality of it the inventors, the scientists, engineers working in advanced economies, they work in the headquarters and they are creating knowledge, working with colleagues. But they also have the ability to work in their home country. If you’re a Taiwanese engineer, you can work with Taiwanese engineers in Taipei as well because you share a lot of culture. You’re much more likely, happy to work with people from Taipei than to work with people from Dusseldorf. You can work with both. But you’re happier, you’re easier to work with people from the country where you came from. These are [00:32:39]bridging ties [0.5s] that you can retain. Right. There are many things here. I’ll just quickly summarise in a single sentence. Multinational inventors, these ethnic inventors, can be a bridge between people in their country of origin and the company they work for. They can. And it’s a two way bridge. They can send out new knowledge from their home country to the country of birth, or they can bring knowledge back from the country of birth to the company they work for. That pipe goes both ways. Okay. They can provide legitimacy to the inventors in the country of origin. Right. Because if you’re sitting in United States and you look at an engineer from Vietnam or engineer from India or Thailand, you might think all these people in these poor countries, they don’t know anything. But if you have somebody from that country who has now legitimacy in your headquarters, that person can now give legitimacy to people from that country, and therefore that knowledge can come in, which might you might have been been dismissive before.

Ram Mudambi [00:33:55] Does it happen? This is all in theory. It could happen, but does it really happen? This is what we studied in a paper that I did some years ago, with Alba Marino, Alessandra Perri, Vittoria Scalera, we look essentially at pattern data and we looked at ethnic inventors and asked the question, “Do ethnic inventors actually act as knowledge bridges within their employing many multinational enterprises? Do they form bridges with inventors in their country of origin? So the empirical strategy was essentially look at patents again. I won’t waste your time going over all the details. We looked at backward citations. This is a standard method of looking at knowledge flows in the innovation management literature. The main challenge was isolating spill-overs. And so we followed a standard strategy in the literature, which is to take matching patents. We took basically patents which had ethnic inventors and matched them to patents that did not have ethnic inventors. We found the global collaborative patterns using a standard methodology outlined by Kerr and Kerr in their 2018 paper. We looked at data from 1975 to 2009. At least one inventor located in the US and another inventor on the team located in an emerging economy. We masked each of those patents with a patent which was matched along many different dimensions but had no ethnic inventor. So are we matching that same application year, the same technology class, cited by the original patent. We looked at about 316,000 citation pairs all together and based on over 3000 for patterns, we use a regression model, linear probability model. And again, quickly to go to the results. Our results were that ethnic inventors do function as knowledge bridges, which is that basically when we matched these patterns, the one that had in it an ethnic inventor what significantly more likely to bridge to knowledge in the home country than one that did not have the ethnic inventor. In other words, if you had a Vietnamese inventor on a patent, it was much more likely that those patents would cite back to patents from Vietnam. Same the Philippines, Thailand, India, any emerging economy for the entire universe of USPTO patents. So this basically showed that we highlight the different the domestic and migrant venters migrant inventors have different kind of value the domestic inventors. But what we demonstrate, I think most importantly, is that [00:37:18]high skilled migrants have two forms of capital. [2.3s] Human capital, their own ability. You yourself, every one of you, you have your own skill. Well, you know what’s in your head. But you also have social capital. Who you know. Who do you know? So somebody asks you a question, maybe you know the answer. That’s your human capital. If you don’t know the answer but you can get your phone and you can call a friend and maybe they have the answer. And now you have the answer. That’s who you know. [00:38:09]What you know [0.4s] and [00:38:10]who you know. [0.2s] You have both.

Ram Mudambi [00:38:13] Now, focusing only on what you know it only gives a partial value of your knowledge. How valuable are you? Right. If I only know two people and if you know 100 people, even if I’m a little smarter than you are, you might be more valuable because you know all the other people, you could tap into 100 different brains, I can only tap two more. Okay. So if I ignore who you know, I’m getting a very partial picture of how valuable you are. This is our message. So my groups are not homogeneous. If I see migrants from a country that has a strong knowledge infrastructure, they can build bridges, ties, they can create knowledge on their own basis, but they can also bring in knowledge from their home country. But if you have another migrant from a country with a very weak knowledge infrastructure, they have nothing to bridge to. It’s not their fault. Right. If I’m from Congo, it’s not my fault. I might be a very smart guy, but there’s nothing in Congo for me to bridge to. I can’t really bring any knowledge from there. Right. That’s not my fault. But that’s the reality. So now if we look at high skill migrants, you should really take the argued two dimensional view. Human capital is measured at the individual level. You get to undergo a high school undergraduate master, Ph.D and so on and look at social capital which is measured at the country of origin, so it values the home country of the inventor. So in case one, we have basically somebody with, say, a master’s degree, from a very low knowedge country versus somebody from a very high knowledge country. In this case, this person is more valuable, right? Because they had the same level of human capital, but they have much higher social capital. They can they can bridge to much more knowledge. Let’s take a more complicated case. So we have somebody from a low knowledge country with a lot of human capital versus somebody from a high knowledge country with less human capital. Say this person as a Ph.D. and this person has a bachelor’s degree. Okay. So who’s more valuable? It’s not clear. If you are at an applied subject like software, it may be the case that a bachelor’s degree is enough and you are much more valuable than the person with a Ph.D. in the same subject if they come from a very basic knowledge country. But it’s not immediately clear.

Ram Mudambi [00:41:37] So let’s look at conflict in country infrastructure. I’ll read the country for you: China, India, Mexico, Egypt, Iran, Kenya and Nigeria. I think these slides can be made available if you’re interested. Look at universities in QS ranking. This is China’s 71 universities. This is a total of the top 1422 universities in the world. 71 are in China, 41 are in India. 32 are in Mexico, 14 in Egypt, six in Iran, one in Kenya. Zero in Nigeria. Top 1000 universities in terms of Google scholar citations. We see 114 of them are in China, 18 in India, five in Mexico, five in Egypt, nine in Iran, zero in Kenya, and zero in Nigeria. Look at the USPTO patent stock by country. China 268,000. India 81,000. Mexico 8000. Egypt. 1000. Iran 575. Kenya 386 and Nigeria 114. These are incredibly different numbers, right? We see that knowledge infrastructure in China and India is hugely larger than any of these other countries. Look at how this correlates directly US patent data. It correlates directly with bridging social capital with the US. These are patents with inventors in the US and in those selected countries. You can see that the blue light is India. The other line is China. India and China, as you can see, are both growing dramatically over time. All the other countries are pretty much close to zero. And that’s the data. All of collect the data together. We see bridging patterns with the U.S. Over 50% are with India. China is about 44%. Everybody else altogether is 6%. Nigeria, zero. In other words, how much knowledge is being created by migrants from those countries and with inventors located in those sending countries. We look at these numbers for the U.S., for example. We don’t have scale there, unfortunately, but that goes into the tens of thousands. The vertical axis number of blue cards issued is running at about less than 100 per year. So high skill blue cards issued out for non EU high skilled workers into Italy is very, very small. These very poor country. Okay. Just about finishing up. If we look at U.S. policy, compared to the U.S. reality. U.S. reality is there were these other visa countries, India and China, other countries where which are creating the most knowledge with U.S. workers. And compare this to the green card, which is the standard of permission to work issued by the United States. China and India, as you can see, have wait times, which are going up to 11, 12, 14 years. So for me, India or China, it’s going to take you 10 to 14 years to get a green card. From Nigeria, your wait time is zero. So basically, if you’re from Nigeria, you come in, if you have an employer, the employer puts an application for a green card, you get it immediately. Of course, inventors of Nigeria have created zero patents with the US.

Ram Mudambi [00:45:43] So this gives us an obvious example of bad policy. The most valuable U.S. migrants face the highest hurdles to entering the US. Maybe wait time from country like Nigeria, Kenya or Iran are low, but the innovation output is also very low. China and India have very high innovation output with the U.S., but the American wait time is very high. All right. So on the face of it, it doesn’t seem to make any sense. So this is not conducive. Certainly this policy is not conducive to innovation and growth. The US is now putting together what’s called the Chips Act or the act that will limit imports of computer chips into the US to maximise U.S. production of chips. But all high tech American companies say they need foreign inventors to produce this knowledge. And if we are restricting the most productive migrants, how can that chips act be successful? Again, we are not talking about humanity or mercy. We’re only talking about producing innovation, high skilled migrants producing innovation. Okay, So I have nothing to say about any other aspect of migration. So since we got nuances in high skill immigration policy, consider local skill shortages when designing policies for innovation. Adopt a points based system that takes both the individual and the individual network into account. Look at the country of origin. That’s a very crude measure, but that’s one way. That’s a start. You can generate points for who should enter. Connect all the knowledge hotspots around the world along the migration highway. Identify the hotspots of innovation in the world we know. We know where the hotspots are. We know Shanghai’s hotspot. We know Bangalore is a hotspot. We know Taipei is a hotspot. So you want to encourage movement between these hotspots and places like Veneto, for example, or Torino. Right. You would like to bring in high skill workers to these places, connect them to other high skilled location. So immigration policy in the end, looking at all the infrastructure and the migrants’ human capital, focuses essentially only on human capital, as we do right now. What we really should be doing is looking at this green box and not emphasising this yellow one as much. Similarly if migrants have low human capital but they come from a high knowledge location, maybe they have some value. So maybe consider this positively. Maybe consider this less positively. Very simple message. The very top. You run these thought on a pretty simple percentage, right? The greatest fruits are the simplest. Any questions or feedback? Grazie mille.

Arabella Mocciaro [00:49:40] So, buonasera, intanto. So, first of all, I’d like to thank Sebastiano for giving me the chance to actually look at this paper and listen to your presentation and I am truly humbled to be discussing a paper of Ram Mudambi who I’ve had the pleasure to read his papers, to listen to him at conferences and I know how much knowledge there is and how much experience there is. So please bear with me if it’s just a set of ideas. So first of all, truly a fabulous paper to expose here in an area in which migration is such a huge topic. So we are certainly one of the hottest areas in migration and the relationship between how firms react and the industrial context of migration is truly central for us. The other aspect is policy. And so how institutions and the definition of policy influence, firm, firm behaviours, incentives and in ultimate issue, firm performance and therefore national performance. I’ll go to that first. Why? Because we have done a whole set of studies on institutions and how that has an effect on innovation and firm strategies. In particular, I am thinking of some studies that we brought ahead with a doctoral student of ours who’s finished her studies now, Elena Nadage and Michele Tumminello and Gabriella Levanti. We’ve looked into how EU policy changes have changed interactions between companies, network structures and innovation performance and tracking how the changes in policies from FP seven to the Horizon 2020 changed showed us that there were three models of change, three different models that came out. One was kind of random partners reassorted randomly. One was path dependent. So you could see an incremental growth in partnerships that tended to reinforce but were still very strong there. And the third was a fact model where there was a recombination of actors. You could see an and render it intelligible, but it wasn’t path dependent strictly. And why is this interesting here? Because we too started thinking perhaps it depends on the knowledge characteristics of the industries in which that’s happening. Okay. So the calls on sustainability could be on health and medical issues or it could be on ageing populations, and that could be very different knowledge paradigms. And so we were saying path dependent could be very strong in, unique paradigmatic fields, whereas few paradigmatic fields would have different ways of having an impact. The other aspect that is similar to this paper is that we also looked at time. So abrupt change and I think that abrupt change is a part of what this model over the year paper was talking about. We looked at abrupt change and we were looking at Covid. What happens when EU policy goes in. So you need to change rapidly. We need a vaccine. And how did that change on the partnerships? And what we saw was, again, another model, very strong path dependence, but also prominence and an attraction to prominence. So when I look at this paper, I think of prominence and time, time and abruptness. And I think that probably two things that I would have looked at in this paper and I’m curious about whether you’ve thought about them. One, I’m sure you have, which is time you see the patent issues from 2000 to 2007, and see what happens and the abrupt change in 2004 visas and how that has an effect. And that’s just 2004-2007 is just three years, right. So probably what you’re looking at is how do companies reassess, reorganise their production process and innovation. But you’re only looking at it in three years. And what that’s brought out is I’m trying to re tap into high skill knowledge places, but I’m having to move people and make them work together through cross boundaries. But if I looked at it on a medium or long term, that may look like a complete reorganisation of innovation activities where I could bring whole areas of innovation, different regions of the world. Therefore, I would not need that tacit knowledge to go through pipelines in different nations. I could keep each one in different regions and then just transport what is transferable in a modular system. So going towards a modularity that would make innovation more efficient.

Arabella Mocciaro [00:54:59] The other point is connected to that. Multinationals that’s true, are the ones that will be tapping in to internet high skill immigrants better than anyone else in the US and probably making the best use of their social capital as well. But the US is not just multinationals. So probably perhaps the companies that are suffering more in also the US may not be just the multinationals, it might be other high tech companies that are not multinationals. And I would be curious to see what has happened to those companies after these immigration policies. So when companies are not able to, in the same time relocate as US multinationals work. Other aspect in the study is that you look at the US as a country with a strong advantage and you connect that to high IP protection and you see that high skilled labour comes from other nations that you don’t really see as a high IP protection area and as such, not high nation specific advantage. And I would say that that is the matrix maybe view in which Italy, you see us as a strong importer of skills, but we are actually unfortunately a highly, highly strong exporter of high skilled labour. We are the brain drain and our area is a brain drain area dramatically. Okay, so we leave that dramatically. And as such, we are not a low IP system. We have a whole load of problems. We have bureaucracy, we have a lot of problems, but not IP protection. So we can be high skilled brain exporters but still high IP. So perhaps attractive. And in that sense, I think it will be interesting. You measure or look at individuals and nations, but companies themselves connect. Right? So it could be not the individual connecting social capital, but the multinational subsidiaries, connecting regions and therefore also individuals. In that sense, therefore, I’d see the locations and not just areas of high skill need or not. Perhaps that’s because we’re Italian, our areas are districts and they’re not just firms that entire of regions in the Saxenian view. So that we have resources and competencies that are in individuals, but in entire areas and companies can insert in themselves, tap into human resources, social capital, tacit resources that they really can take advantage of when they decide to actually locate there and invest there. So they can tap into that for sure. The other aspect is they can invest into it and build towards it in that idea of sustainability idea and not just of a, you know, philanthropy, but a shared value where I actually am investing in locations that are not the US, that are not the country may, but they are somewhere in between and building into that knowledge system, investing into it to build it, but not to the advantage of the area only, but to the advantage of the whole company feeding back into my competitive advantage. And only a multinational can really do that. So I think this paper is somehow not emphasising that I know you know much too well that it’s not wanting to emphasise that aspect, which I understand this is in some way wanted.

Arabella Mocciaro [00:59:04] So the other thing is that I’d say that when you look at this as a policy point of view, and I think that when you end up that the truth is very simple. I mean, of course it’s very simple. Human resources are the number one resource for a nation to advance. So limiting high skilled immigration is just nonsense. Right? Okay. So but seen from our perspective, where we are high skilled brain drainers, we actually see this as a huge opportunity. Right? So in our view, we are hoping that those policies go ahead and that multinational companies will want to relocate and invest here and tap into our knowledge and this is happening. So we’re seeing high world class consulting companies deciding that they’re going to change their model and locate the highest centres for innovation and consultancy, not where the clients are, but actually where the talents are. And so we’re hoping that that’s going to be a very strong, attractive factor for the companies who can complement our smaller companies that often don’t have enough resources, financial resources, physical resources or connection to the international markets to tap into our talents, build into our systems, create and sustain, help us sustain the competitiveness of our entities here, and then bring it worldwide in the markets to their advantage and to us. So I’d say that this is probably what I wanted to underline most of this paper, and I’d say that the multinational companies, given that this policy is a not is, is not okay. So that policy is bad. But saying it, multinational companies, we’re actually hoping will move to tap into the nations, not just bring people that way. So thank you very much for this opportunity.

Paolo Li Donni [01:01:12] So what do you mean? And I’m very glad two days is short, especially to do this paper. Actually, I’m not keen at all on this topic on migration. It’s not my field and it will not be also, by the way. And I will go directly to the main topic and to the paper itself. The standard in immigration policy for what I understood in the last couple of days is basically based on the human capital. There is a very nice paper from Hadda which basically identified two different aspects of this human capital. The accumulated work experience, which basically means qualification, education and blah, blah, blah. And also the host country specific human capital. I think that these two elements are the main key elements which identify the human capital, which is used in the policy for immigration that are used in the country. Okay. The paper basically says human capital is not the only relevant factors. There is also some other stuff which are import and one of these elements is the social capital, which is also relevant. So the conclusion from a policy implication for what I understood is basically that an immigration policy should promote or simplify migration for high skilled workers from country with relatively high social capital. And I think that this is very intuitive. And actually the paper makes a very good job in identifying and explaining, supporting and so on, these very clear and simple idea. But I had actually some question, doubts because, okay, human high skilled immigrants are really important, but also low skilled immigrants are important. So the first one is social capital is a measure which is provided at county level. Okay? Now the country level measure, it’s not under control of immigrants, but he will pay the cost actually, of using these criteria on adding assets to a country. So you are making someone pay for something that he is not entitled to. The second point is, I think, how to find a fair balance between human and social capital in order to do something like that in a policy. The second element sees into the into using social capital to evaluate a green card application might work very well for high skill immigrants. So look at some very recent historical facts. For example, in the north of Italy in 1990s, immigrants filled many manual labour intensive jobs that had gone unfilled, so you need basically some low skilled immigrants to make some of these jobs. Same story with Greece. Greece during the last 20 years basically has a bailout and blah, blah, blah. And also in that case, the immigrants helped to sustain their economy. How does in this case social capital criteria deal with the demand of low skilled workers, in this case? Third one, to look at the social capital criteria penalise low skill immigration by definition by construction, or at least you do not know the effects in advance. So with labour intensive jobs native workers are able to specialise and upgrade they own skills and is very well known by some papers. Now in Italy for example the low skilled immigrant women provided household services that enable high skilled and native to spend more time at work. So basically native workers can invest in themselves . So also in this case what is that fact of specialisation and upgrading when you made the social capital criteria as the main pillar of the immigration policy. The last one which is basically the downward slope function that we saw before when you have the two cases. The major problem and that effect would be the smallest volume, sort of the fact that I think it’s being occupied by. Else also much more of the I’m sorry you called the factual evidence in the case of the of this of this. So to thank you.

Ram Mudambi [01:07:03] First of all, I’d like to thank all 3 million for absolutely wonderful comments. And I would like to take this opportunity to quickly respond, obviously. Many detailed comments. I don’t want to waste I don’t want I don’t want to take time from the audience to respond to each and every comment. But quickly, two main responses. The first I think I think I and Paula made a common comment, which is. Which I interpret to mean that the country level measure of social capital is too blunt and too crude. Obviously, everybody from Country X, Thailand, for example, is not the same. And they all don’t have the same social capital. There is a fairness aspect, I think that I mentioned, which is that you can’t control that in your country of origin. However. This was written from a policy with a policy maker in mind, and therefore we were looking for the simplest thing you could use. And country of origin is very simple and very difficult to change. However, if I were to try and make this a better policy and also I think we could think about this in terms of our paper itself, I would ultimately. I think I stand by my example of social capital being ultimately something your network person that what you can you can control. You can control your social network people that you know right now. How can they do that? Obviously I can’t take everybody’s phone as a policymaker and check their social capital. But what we can do is we can take a look at finer measures of social capital. One thing, for example, that we know or I know from my own research, my own studies looking at Indian immigration to the US is that our very, very few elite.

Speaker 3 [01:09:10] Spiritual institutions in India that provide the vast majority of success story for you. Okay, There are like maybe 5 or 6 institutions. And these guys, this entire network that has been built up over the last two years, 50 years, they all know each other or each other and so on. And so you can see, you know, the education. And so we bring down the big policy barrier by saying, okay, well, you identify certain institutions and people, this is on your CV. Then you get your points. And this you can control it. You can control where you go to university. You can’t control your. Which you can control, where you want you to work. Similarly, in your company you can control when you work for it. Fact when we interviewed in Bangalore found that most entrepreneurs.

Ram Mudambi [01:10:15] Said they.

Speaker 3 [01:10:16] Set a starting, successful, starting very successful company. I always I went to the government my personal. But I knew I wouldn’t be wanting to be there for three years because I wanted to put on my seat that I had Microsoft and that I knew what microphone one at the time it worked on, if I ever thought that I had company. That again, you can see and get points for that. Who you work for, you can control that. Third and final point. You mentioned the issue of high school versus low skill and people. I think you can have divided Muslim workers, but those can work. That is made by human get. First of all, not my first. All right. So already our point system already. So we have a method going in on this. We’re not really going to think about. So that concludes the show. Marketing. Very important. Very nice. Actually, the cost of goods between March and April of 1962. So I see. Points squared. Never enough friends. So. Well. So I just want to say I haven’t read more about you. And so from what’s actually said here today, and from what I would say, you are reasonable. You are mostly focusing on a very tiny subset of my my own people, not only minor people, So very tiny subset of my people, but by which I mean my migrants, which I would say are 5% of migrant people. They might be trifle, but yeah. Anyway, I slice weeds and you are very nice, Julianne. Very harsh, Yes. Mark Next, I ask. I absolutely agree with it, which is nice. You be. But the part that I am sure you will be confused is when you try and use this theory and this evidence in order to explain all of this, we actually have to do not only read migrants but downwards. We might be completely back in the middle and lose in my brother and my. And so I actually wants to be good. So this is really to be honest and to be very high frequency. All right. Thanks very much. That’s a very good point. From what I’m hearing that the respective of both the Senate, I think that’s almost the recommendation. And the ultimately are from the perspective of the preceding.

Ram Mudambi [01:13:22] Which are which countries. And we are we’re basically saying that ultimately the sending countries are not restricting rights, the poor countries not restricting people from leaving generally, especially when they’re leaving for a better life, is ultimately the receiving countries that are putting the restrictions. So the parliaments, the policy where if the U.S. were to admit more people, more people would come. Right. So that’s what we’re focusing on in the first place. Now, you ask what about what about low skill and medium skill individuals? From the perspective of the. Well, from the receiving country, it is quite clear that high skilled workers are more valuable than low skilled workers. Okay. There is, I think, a lot of it. I’ll tell you, I work for people like Moretti and show and show that ultimately when you bring high, high skill foreign work with immigrants, they start companies. They companies employ people, they employ low skill people, a native born as well. And so overall, there is a benefit When you have high skilled migrants come in, there’s a benefit for the country in terms of knowledge creation, but also in terms of wealth creation for low skill, native born people, okay, because they get employed in these companies, they get started. It is also the case for the sending country that they gain more by sending high skilled as compared to sending low skilled. Okay. Now basically that the data for any I guess that I study India like look at India data India is basically again bear the truth is very complicated but the very simple story simple reality is that high skilled Indian migrants go to Europe and North America. Low skill Indian migrants go to the Middle East, to Arabia and the UAE and so on and so forth. The low skilled migrants send money back home to their relatives. High skilled migrants send investment of their companies back to India. So you send low skilled migrant to Arabia who sends back €1,000. You send a high skilled migrant and you send out €1,000 immediately. You send a high skilled migrant to the US. 20 years later, you bring back $100 million of investment. So it is more valid for India to send a high skill migrant than to send a low skilled migrant. And it’s more valuable for the U.S. to get a high skill migrant than to get a low skilled migrant. So it’s a win win for everybody to send high skilled migrants abroad as compared to low skilled migrants. Okay. So in other words, now you ask what should a well, low skilled versus high skilled migrant available? You say that the fairness issue is, is what other kind of issue is it ultimately economics that we’re talking ultimately here, not about normative economics, but about positive economics? The positive economics is that the world gains more, both the sending and the receiving countries by having high skilled migrants. Right. Everybody gains more by sending high school migrant, they get less. By having low skill migrants. And so simply in terms of euros, dollars, GDP, it is better for high skill migrants to move and to block low skill migrants from moving. Okay. So long is the better life story if it’s a question of persecution. That is a completely different calculus. We’re no longer talking about GDP. We’re not talking about creating jobs in North Korea or creating wealth. We’re talking mercy. And humanity is a different story. And that’s a that is not that that should not that should not be confused with this. Okay. Am I? That makes sense to you?

Speaker 3 [01:17:27] Yeah. No. Yeah. Thank you. Most of what I see my office are. Yes, pretty mobile, but they’re very, very tiny. Yeah. And me? We have like that. I know that. For me, you know, in life mind, I know it’s never happened before.

Ram Mudambi [01:17:54] Okay. The important thing is leverage. Let me give you one example. Elon Musk is one person from South Africa to the US, and he has created in the United States hundreds of thousands of jobs. Yeah. Yeah.

Speaker 3 [01:18:14] You know, so not only was he never before been quite.

Ram Mudambi [01:18:20] Well, he went to Penn. Yes. Yeah. Okay. And then admittedly. But there are lots of I could give you examples of Indian migrants who came to the U.S. with €500 in the pocket, and they created 50,000 jobs. 80,000 jobs. Okay. So it is a question of how much is created by the one person. Okay. So very few people create a lot of value and employ a lot of low skilled workers. And many of these companies go back and employ a lot of the workers in the home country as well. Okay, So now let’s go to the Italian case for a minute, because I think Paolo mentioned a lot about northern Italy, southern Italy, and I know a little bit about the police and I know very little about Italy. But if you look at the migration in Italy from south to north. There’s a lot of remittances going on for at least for a generation. Right. There is sort of money coming back and wealth and wealth transfer occurred and so on. But to the best of my knowledge and I fully I could be ignorant, but to the best of my knowledge, there is not a incentive system in it seems to me, for example, to encourage connections of those individuals back to their home location, through the company or through some kind of enter, some kind of policy or some kind of circulatory circulation mechanism whereby you can build connections, say within Italy or indeed otherwise. I mentioned Italy, Italy being an exporter of grapes. There are lots and lots to eat, academia, high skill Italians in all of Europe. But there is, to the best of my knowledge, no great policy to connect them back to say they work for Philips or they worked for a Daimler-Benz. Shouldn’t you think of them being sources of FDI, foreign direct investment into Italy? Leveraging that connection because they were just like the Indian wanted to invest in India. Clearly they want to invest in Italy, but there should be a way for that to happen or a policy for that to happen.

Speaker 2 [01:20:44] Okay. And when you’re talking about Graziano, thank you very much. I’m.

Ram Mudambi [01:21:07] Vibrant all.

Speaker 3 [01:21:10] Language. Right.

Paolo Li Donni [01:21:13] And I think they should. And I hope to see you again.

Ram Mudambi [01:21:16] I certainly would hope. I really I can say that.

Questo contenuto è stato scritto da un utente della Community. Il responsabile della pubblicazione è esclusivamente il suo autore.